You Need A Hobby. No, Really.

A few years before my divorce—when my marriage had hit the iceberg but the hopeful and doomed band was still playing—I sat in a counseling session with my then-husband and our therapist. The discussion revolved around free time: My inequitable lack of it, and my ability to do anything meaningful with what precious little I might be given.

“What do you like to do for fun, Julia?” our mild-mannered (also hopeful and doomed) counselor asked. “What are your interests?” The truth was embarrassing and infuriating: I didn’t know anymore.

Primary caregivers of young kids might understand. My daughter was under three years old at the time, and all of my energy was spent caring for her while running my just-launched boutique copywriting business. My “free” time—a few weekend hours—wasn’t really mine anymore: It was filled with kid-related or family-centered activities that had nothing to do with me as an individual person. Everything I did, even my hobbies, revolved around them.

Save the McFlys

Without realizing it, the woman I had been before my husband, before my daughter, and before the move to the suburbs had started to fade—like that picture of Marty McFly and his siblings in Back To The Future. In service to my family, I was losing her. And worse, I thought I had to.

Coming back to myself felt daunting, but it was clear. I needed a goddamn hobby.

One night, after my daughter had gone to bed and her father was at work I turned on The Great British Baking Show to try to learn how to make a Victoria sponge (baking: a former hobby I was trying to resurrect). I was taken aback as they introduced the contestants. “Liam is a blacksmith from North Chestershireington who enjoys kayaking, wood widdling, and playing drums in a band,” “Marge is a primary school nurse who plays roller derby and won her town’s poetry slam contest three years running.”

They did all of this—and they could make a Victoria sponge? Here I thought just baking was the hobby.

Each contestant seemed fulfilled and happy, even-keeled and energetic. I felt like they had cracked a code: They had hobbies that were as important in the hierarchy of their life as their day jobs, and they made the appropriate amount of space to enjoy them. In turn, having that time to realize the things they loved doing made them love everything they did just a little bit more. They weren’t even hobbies anymore— they were life.

That was what I needed—to weave the threads of individual enjoyment into the everyday. Challenge accepted.

An image from the "before" times, when I went to an all-women's retreat in Oahu to learn to surf.

My initial strategy was to gravitate to the familiar, to go back to the things I enjoyed I the “before times,” but trying to capture the magic of long-loved activities during this new era felt forced. Instead, I chose to practice an awareness: Catching that fleeting moment when I felt happiness, joy, serenity, or amusement while engaged in an activity. Then, I would try to do that thing more, and make it multiply.

This years-long process was filled with trial and error. I ran a half marathon (alone, in a pandemic, to raise money for first responders) and read a lot of terrible books, and some great ones, too. (I even wrote one, stay tuned for it to hit shelves in August 2025!) I got back into crosswords and trivia, and started making playlists and going to concerts again, often alone. Now, if I can and she’s into it, I bring my daughter. I watched documentaries and did puzzles; listened to podcasts on everything I had even a passing interest in. I bought a cross-stitch pattern that actually teaches you cross-stitch, and then I never opened it. I’m learning tarot card reading. I did diamond art and tried my hand at gardening—I think plants probably still tremble when they see me coming. Who can kill a cactus? That would be me. I’ve failed more than I’ve succeeded, but I keep trying because the success of finding those bits of happiness in my everyday make it so worth it.

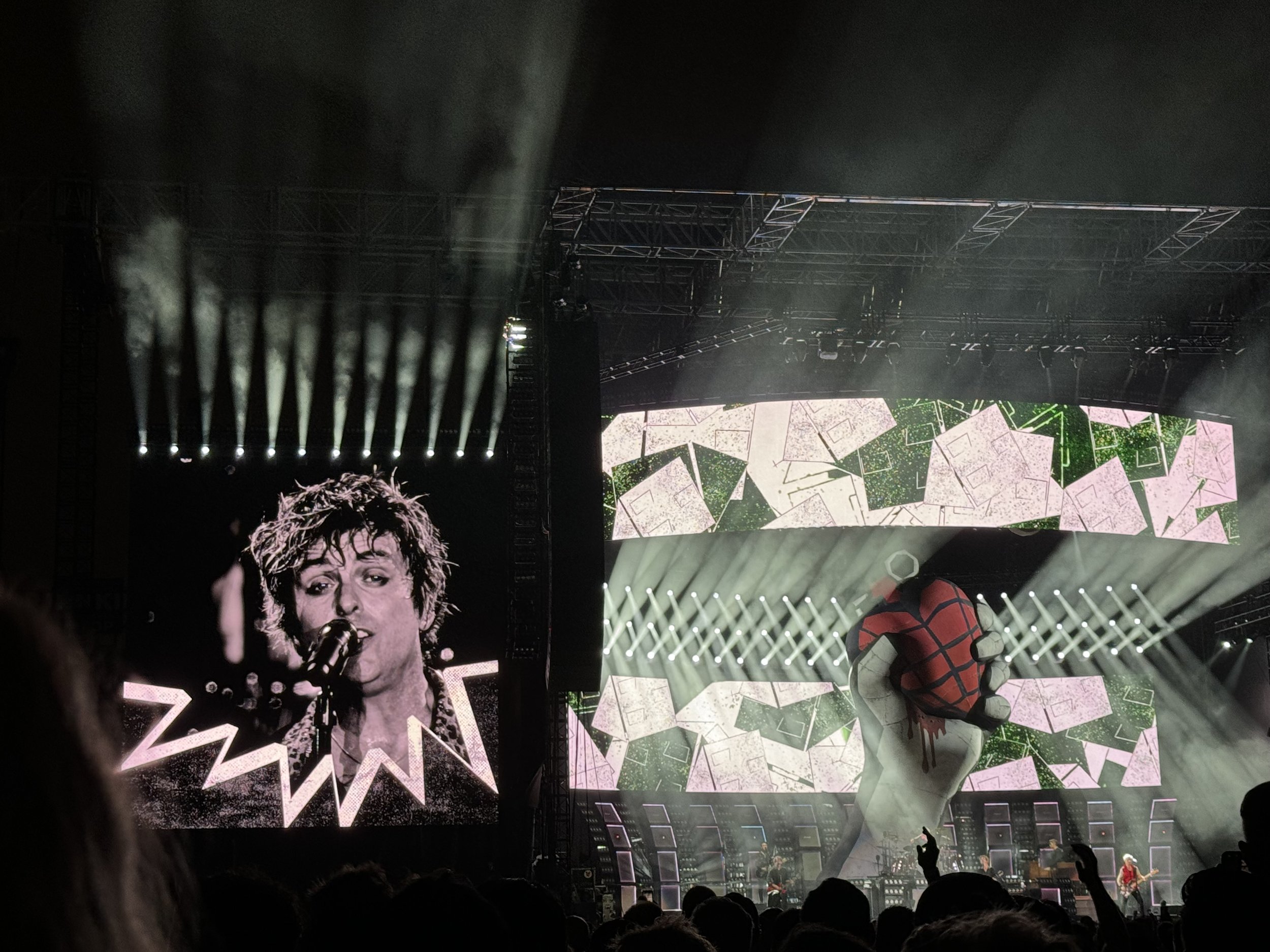

Mother-Daughter Green Day Concert, August 2024

The same year of the divorce, my father died. To craft his obituary I went back over others I had written at the request of friends through the years. The same thing stood out time and again: What defines a life is who and what we love. What brings us light? I think of the woman who played Scrabble with her girlfriends every day. The man on the bowling league who biked to work every day. I think about my dad, organizing our block parties in Brooklyn, enjoying a coffee on the back deck, or retreating with his book to the shoreline on a sunny beach day. Obituaries don’t read like resumes. They read like life.

To paraphrase Glennon Doyle: Do I want to spend my one wild and precious life ignoring my opportunities for joy?

Making room for joy in our lives through hobbies that are ours, really ours, is so critical to our true happiness. It fills us with gratitude, it helps us avoid burnout. It makes us better, happier people to the ones around us. It makes us more engaged at work, and more engaged outside of it. It takes us out of our work/grind headspace and reminds us that life is for the living. And then, counterintuitively, it makes us better, more creative, and more thoughtful in our day jobs.

I have no science for this, my research is purely anecdotal. But trust me.

So when we next meet, here’s something: don’t tell me what you do for a living. Tell me what living you’re doing.